Home » Resources » Research & Data » Deaf College Student Data » 2018-2019 Deaf College Student National Accessibility Report

ACCESS Is More Than Accommodations

2018-2019 Deaf College Student National Accessibility Report

This is an overview of the experiences of deaf college students in the 2018-2019 academic year. For more current information, visit the Deaf Postsecondary Access and Inclusion Survey page.

Palmer, J. L., Cawthon, S. W., Garberoglio, C. L., & Ivanko, T. (2019). ACCESS is more than accommodations: 2018–2019 deaf college student national accessibility report. National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, The University of Texas at Austin.

This publication was developed under a jointly funded grant through the Office of Special Education Programs and the Rehabilitation Services Administration, #H326D160001. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the federal government.

Quotes throughout are from students’ responses to open-ended questions in the survey.

Electronic versions of this report and all other National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes (NDC) data reports are available here.

The authors first wish to thank the deaf students who participated in our survey for enlightening us about their postsecondary experiences. We are thankful to the organizations and stakeholders that helped disseminate information about the survey. We also wish to acknowledge NDC Research and Data graduate assistants Paige Johnson, Claire Ryan, and Savannah Davidson for their work on survey development. We are also thankful for our NDC colleagues who provided thoughtful feedback and continual support throughout the survey development and data collection process.

NDC is a technical assistance and dissemination center supported by a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs. NDC provides evidence-based strategies to deaf individuals, family members, and professionals at the local, state, and national levels with the goal of closing education and employment gaps for deaf individuals.

Table of Contents

Key Findings

During the 2018–2019 academic year, the National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes (NDC) surveyed deaf students in higher education institutions across the nation. This report provides a comprehensive overview of results from that survey and offers suggestions for improving access and inclusion on campus for deaf students. The survey targets six key indicators of access and inclusion and provides data on the experience of more than 300 deaf college students.

Achieving Certification

Overall Rating 3.2 of 5

Attitudes 3.5 out of 5

Campus Technology 2.9 out of 5

Communications 3.3 out of 5

Overall Rating 3.2 of 5

Attitudes 3.5 out of 5

Campus Technology 2.9 out of 5

Communications 3.3 out of 5

Students Who Reported the Highest Ratings

Deaf students without additional disabilities

Deaf students who had more than one accommodation

Key Recommendations

Evaluate Current Institutional Practices

Identify existing barriers, challenges, and limitations on your campus. Evaluate the institution’s overall capacity to provide opportunities for deaf students to engage with people and participate in all activities, programs, and services on campus. This information is a baseline for understanding what your institution does well and which areas are in need of improvement.

Target and Prioritize Areas of Improvement

Consider the impact of improvements, resources available to create change, and alignment of initiatives with the institution’s mission. Identify specific actionable steps, a timeframe for completion, and a staff member to monitor and report progress.

Share Strengths and Concerns Regarding Access with the Larger College Community

Access is not the responsibility of one department; it is a community responsibility. Most people on a college campus do not realize how they contribute to access barriers and do not know how that can be changed. Seek opportunities to communicate with students, faculty members, and administrators about what the institution is doing well and where improvements are needed.

Seek Opportunities for Collaboration and Partnership

Explore opportunities to leverage resources and relationships, on campus and within the community, to increase individual and institutional capacity for inclusion and access. Highlight the relevance of these issues not only to deaf students, but also to the entire community. Seek alignment with departmental or various stakeholder groups’ goals across campus, then combine efforts and resources to spur change.

Deaf People Are Going to College. Are Colleges Ready?

Postsecondary education is important for many reasons, including achieving long-term financial stability and career satisfaction, enhancing personal and professional networks, and becoming a more engaged and productive member of society. Nearly 70% of all high school graduates enroll in colleges or universities (Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2019). Current trends indicate that more students are choosing to pursue education and training after high school to support their long-term career goals. As colleges and universities embrace a more diverse student body, there are opportunities to make campus a welcoming environment for students who traditionally have been excluded from higher education.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, more than 19% of undergraduate students have disabilities (Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, 2019). Among currently enrolled students with disabilities, 1 in 25 is deaf (Garberoglio, Palmer, & Cawthon, 2019).

Redefining ACCESS

The traditional model of access provides accommodations for deaf students so they can access auditory information in the classroom. The problem with this model is that providing this basic level of accommodations in the classroom does not guarantee that deaf students have full access to the broader learning environment and does not always facilitate positive outcomes (Cawthon et al., 2020).

Using a systematic approach rooted in research and literature to ascertain the best available evidence related to providing access to deaf students, NDC identified six key components of access: Attitudes, Campus Technology, Communications, Environment, Services, and Social Engagement.

Attitudes

A campus climate that welcomes and integrates deaf students in all aspects of campus life.

Campus Technology

Flexible technologies that are readily available in all campus settings—from classrooms to locker rooms—for deaf students to fully access and experience the college environment.

Communications

Efficient and effective communication and information delivery that allows deaf students to maximize formal and informal learning opportunities.

Environment

Accessible physical and online spaces that accommodate and adapt to a wide variety of deaf student experiences.

Services

Comprehensive accommodations for deaf students that are readily available, reliably provided, individually customized, and monitored for quality and success.

Social Engagement

The complete immersion in a campus experience that seamlessly includes deaf students in all events and opportunities to socialize, network, and connect.

The ACCESS Survey

NDC surveyed deaf students in higher education institutions across the nation. The aim was to evaluate accessibility on campus, considering not only the traditional definition of access and accommodations, but also indicators of whether deaf students felt engaged and supported at school. This report provides a comprehensive overview of the results from the survey and offers suggestions for improving access and inclusion on campus for deaf students.

The goal was to develop a robust measure of access that could be used repeatedly to inform areas of focus and improvement. The ACCESS survey asked students questions about access and inclusion. The questions were presented bilingually in English and American Sign Language.

Who Took This Survey?

Deaf students enrolled in any postsecondary training or educational program in the United States who are at least 18 years old were eligible to take the survey. The sample in this report consisted of 302 students attending 122 colleges and universities in nearly all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Survey respondents ranged from 19 to 66 years old, with an average age of 29. This aligns with national data showing that deaf undergraduate students have an average age of 31, while their hearing peers have an average age of 26 (Garberoglio, Palmer, & Cawthon, 2019). This report does not include data from students attending institutions that historically serve deaf students (Gallaudet University, National Technical Institute for the Deaf). For more information on the students who took this survey, see the Demographics section later in this report.

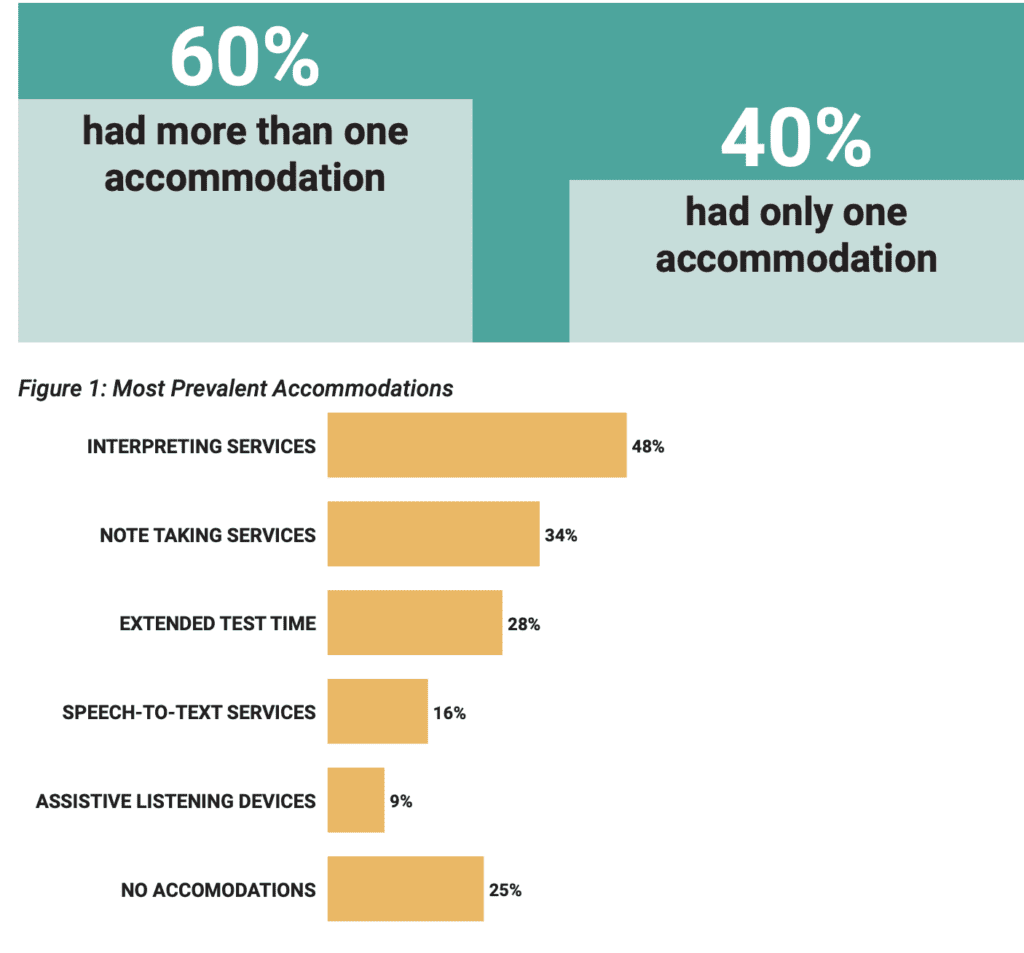

What Accommodations Do Deaf Students Use in College?

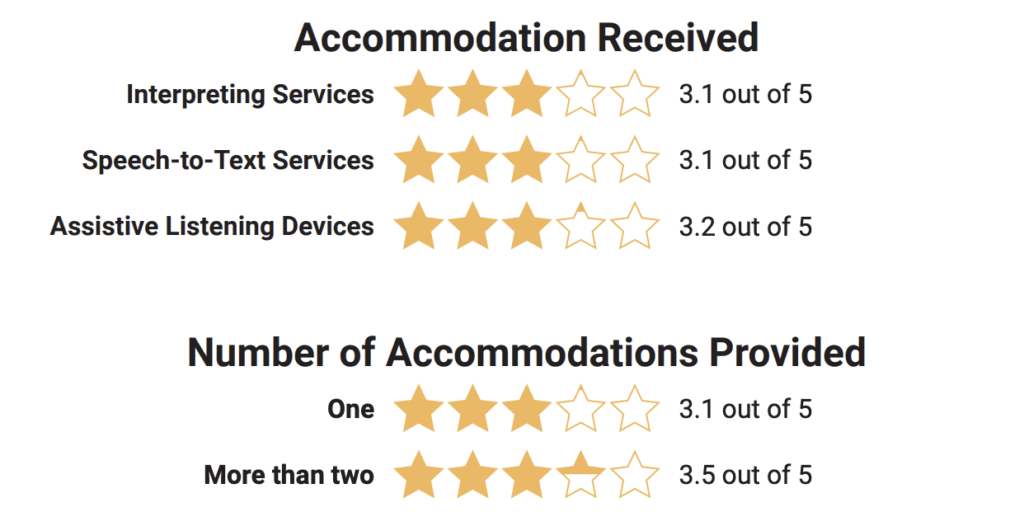

Combinations of Accommodations

- Of the 144 students who received interpreting services, 47% also used note taking, 32% used extended time, 22% used speech-to-text services, and less than 1% used assistive listening systems.

- Of the 49 students who received speech-to-text services, 63% also used interpreting, 39% used extended time, 37% used note-taking, 20% used assisted listening, and 16% used another accommodation.

- Of 27 students who used assistive listening systems, 70% also used extended test time, 59% used note taking services, 37% used interpreting, 37% used speech-to-text services, and 19% used another accommodation.

How Accessible Are Campuses for Deaf Students?

Access is more than accommodations. For deaf students, a campus can feel welcoming and inviting or frustrating and isolating.

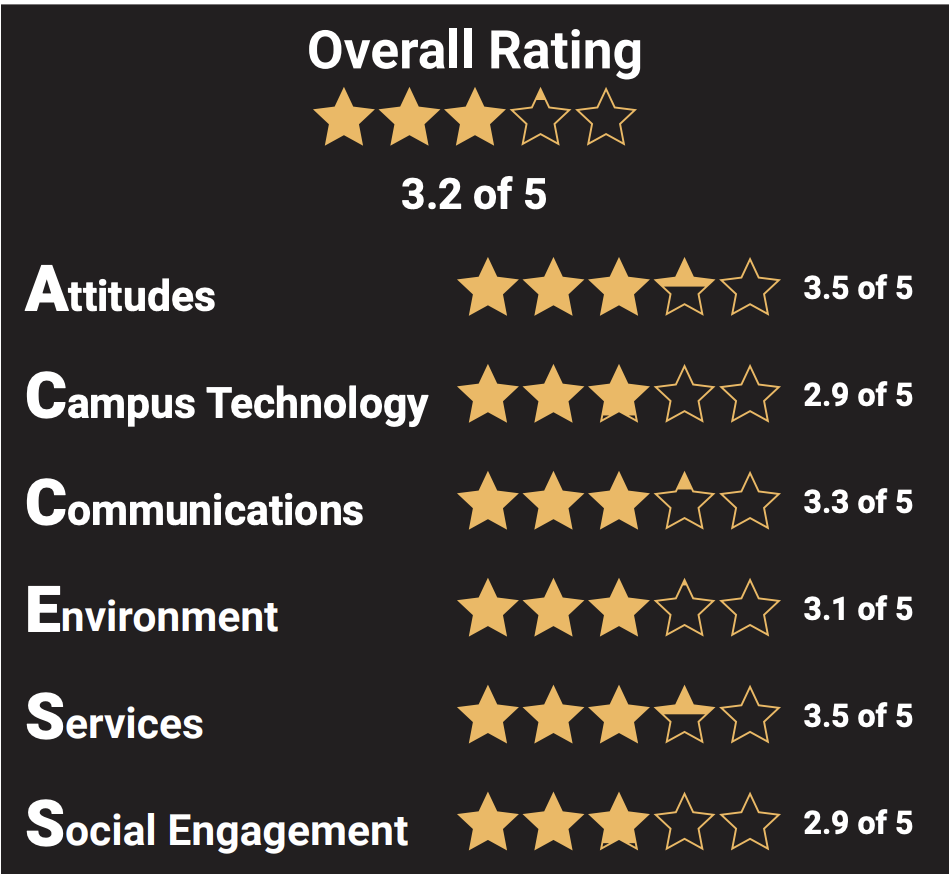

Overall, deaf students surveyed did not provide favorable ratings of accessibility of their postsecondary education and training environments. On average, survey respondents rated their institutions 3.2 out of 5. This finding suggests a lot of room for improvement in the college experiences of deaf students across the nation.

The ACCESS survey provides a framework for considering institutional improvement activities. Average ratings varied across the six ACCESS categories. Survey participants rated Attitudes on campus and Services the highest, followed by Communications, Environment, Social Engagement, and Campus Technology.

Negative perceptions and attitudes about deaf students on campus can deter motivation in the classroom and add unnecessary obstacles to receiving appropriate supports and accommodations. The attitudes of teachers and other professionals influence how deaf individuals view themselves, and can affect their goals (Crowe, McLeod, McKinnon, & Ching, 2015; Smith, 2013). The attitudes of peers can influence how deaf students engage in social and academic activities (Vignes et al., 2009).

Negative perceptions and attitudes about deaf students on campus can deter motivation in the classroom and add unnecessary obstacles to receiving appropriate supports and accommodations. The attitudes of teachers and other professionals influence how deaf individuals view themselves, and can affect their goals (Crowe, McLeod, McKinnon, & Ching, 2015; Smith, 2013). The attitudes of peers can influence how deaf students engage in social and academic activities (Vignes et al., 2009).

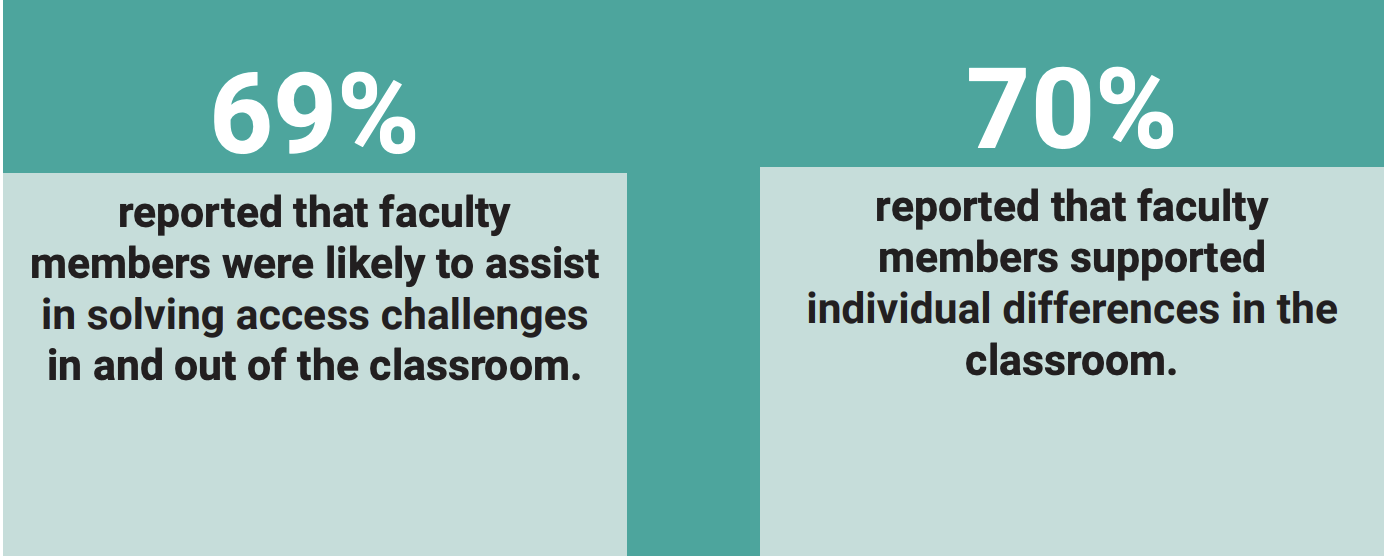

Survey participants rated Attitudes on campus at 3.5 out of 5. For this component, we asked students questions such as whether they feel welcome engaging in conversations with their classmates and whether faculty members are supportive of individual differences and diverse perspectives in the classroom.

“At this point, I’ve decided to stop talking to disability services because their answer is always no.”

Technology is widely used on campuses. There are two main types of technology in the classroom: technology to support learning, and technology to support access and communication.

Technology is widely used on campuses. There are two main types of technology in the classroom: technology to support learning, and technology to support access and communication.

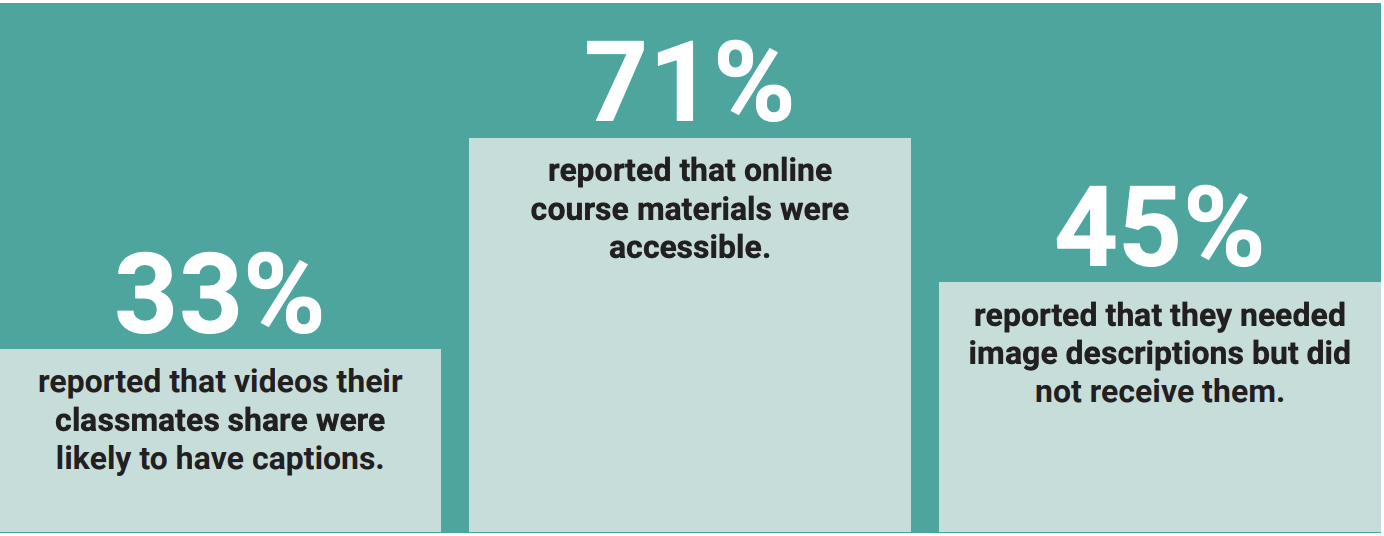

This component of the ACCESS survey asks students about their experiences with technologies across campus. For example, we asked students whether faculty members used technology-based live polls during class to encourage classroom participation and whether online course materials were likely to be accessible. On average, students rated Campus Technology at 2.9.

“All of my courses are online, and I don’t always get captions and transcripts in a timely manner. I usually have to wait 3 weeks (or more) to get access to materials, and sometimes, I never get them at all.”

Accessibility is often linked to communication for deaf students. Communication access to direct instruction and support, and also to incidental learning opportunities, is critical for postsecondary success (Brackenbury et al., 2005; Lederberg, Prezbindowski, & Spencer, 2000).

Accessibility is often linked to communication for deaf students. Communication access to direct instruction and support, and also to incidental learning opportunities, is critical for postsecondary success (Brackenbury et al., 2005; Lederberg, Prezbindowski, & Spencer, 2000).

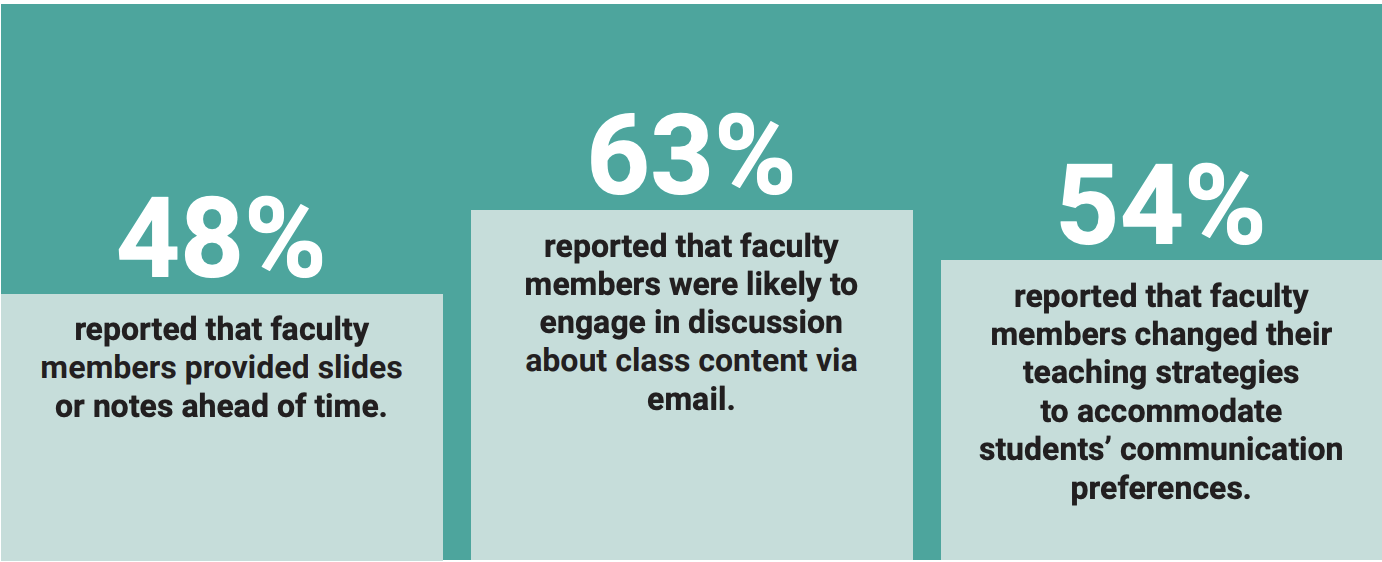

We asked survey respondents several questions about how course content and various types of information is relayed to them. For example, we asked whether faculty members were likely to supplement lectures with slides and handouts and whether classmates worked collaboratively to ensure access during group work. On average, students rated Communications at 3.3.

“Most of the faculty and students are ignorant about Deaf culture, so it’s a constant battle to explain myself … that they need to slow down … that they have to write certain things down and that I have trouble lip reading. It’s frustrating.”

In addition to things like automatic doors and wide sidewalks, physical access includes accessible sight lines, accessible doorbells, visual alarms, and accessible notification systems. The concept of “deaf space” is an essential part of access for deaf students that helps us think beyond merely installing visual fire alarms. Deaf space asks us to think more deeply about how deaf people navigate physical space, considering visual space, sight lines, light, color, and acoustics (Bauman, 2014; Edwards & Harold, 2014).

In addition to things like automatic doors and wide sidewalks, physical access includes accessible sight lines, accessible doorbells, visual alarms, and accessible notification systems. The concept of “deaf space” is an essential part of access for deaf students that helps us think beyond merely installing visual fire alarms. Deaf space asks us to think more deeply about how deaf people navigate physical space, considering visual space, sight lines, light, color, and acoustics (Bauman, 2014; Edwards & Harold, 2014).

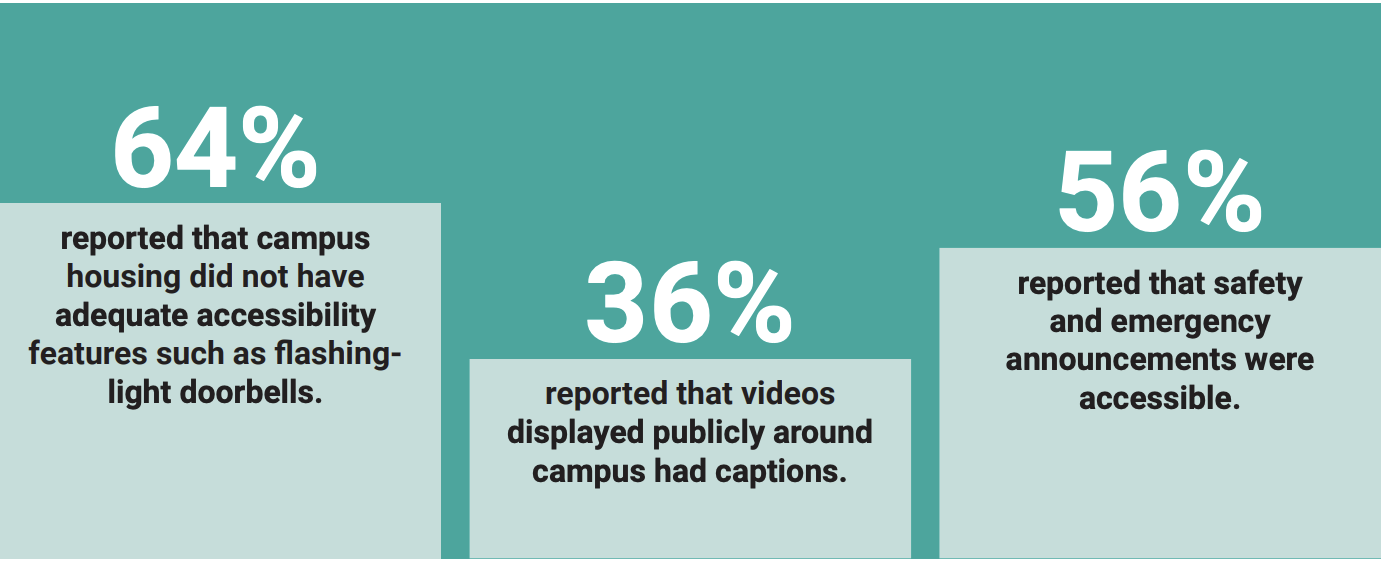

For this component of the ACCESS framework, we asked deaf students whether classrooms were likely to be free of excess distracting noise (e.g., loud fans, echoes) and whether videos on campus were likely to have captions. Overall, students rated Environment at 3.1.

“Asking professors to manage side conversations in the classroom to keep the background noise at a minimum is seen by some instructors as counterproductive to their efforts to connect with students.”

Providing accommodations includes scheduling and coordinating services such as interpreting, speech-to-text services, modified instruction, tutoring, and extra time for tests. Accommodations provided for deaf students vary according to individual needs and preferences and often change by setting (Cawthon & Leppo, 2013).

Providing accommodations includes scheduling and coordinating services such as interpreting, speech-to-text services, modified instruction, tutoring, and extra time for tests. Accommodations provided for deaf students vary according to individual needs and preferences and often change by setting (Cawthon & Leppo, 2013).

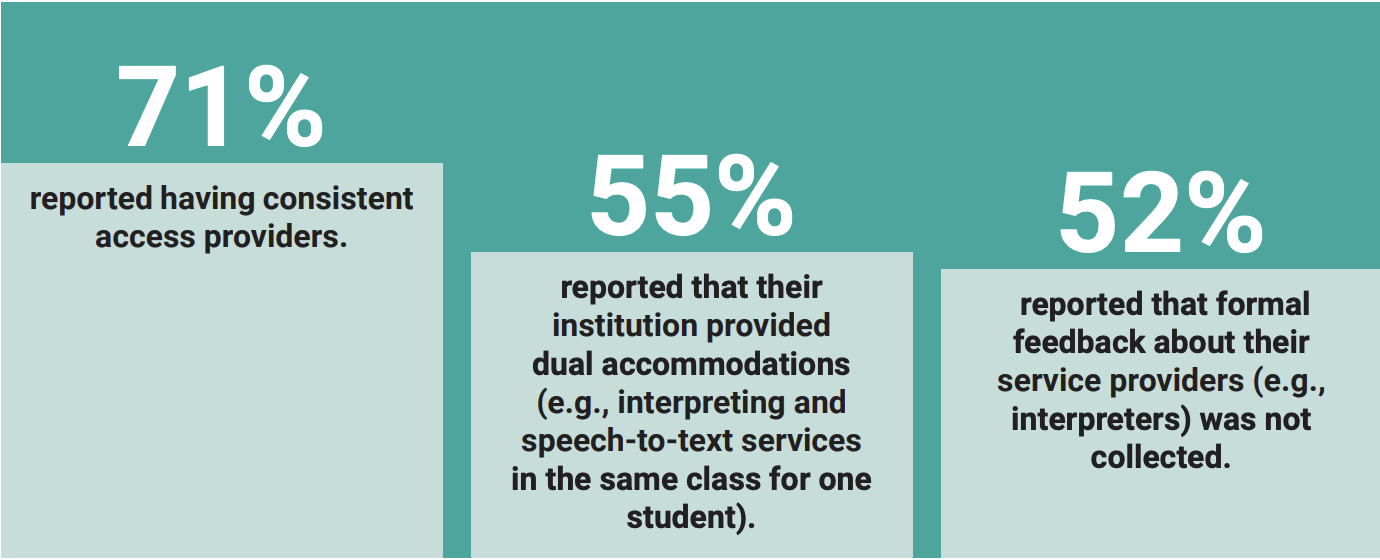

In the survey, we asked students several questions about the provision of services. For example, we asked whether the disability service office responds to requests in a timely manner and collects formal feedback about service providers. On average, students rated Services at 3.5.

“It is not often that I have ASL interpreters who can keep up with me (voicing for me), so I find myself having to take the extra time to explain concepts to them.”

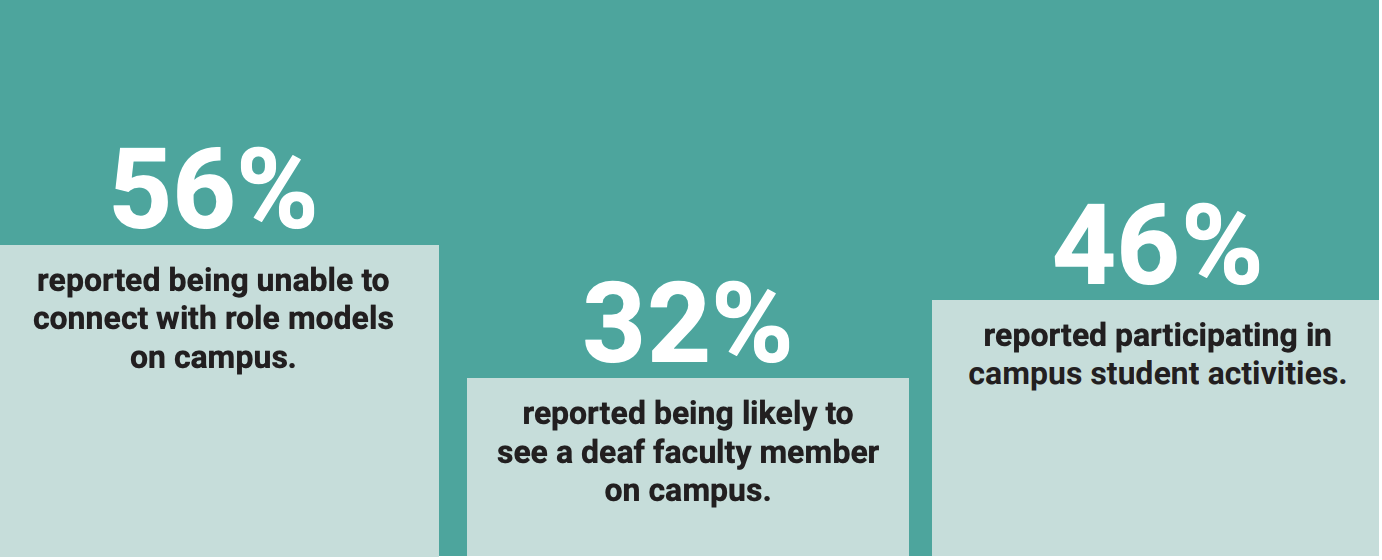

Students build social capital when they develop relationships and networks based on shared values that allow them to exchange information and resources (Yosso, 2005). Accessible social networks are valuable for deaf individuals to share tips, strategies, and tools to navigate campus life (Covell, 2007; Hintermair, 2008). The full inclusion of deaf students means that social networks are accessible, both in person and online, and in both formal and informal settings.

Students build social capital when they develop relationships and networks based on shared values that allow them to exchange information and resources (Yosso, 2005). Accessible social networks are valuable for deaf individuals to share tips, strategies, and tools to navigate campus life (Covell, 2007; Hintermair, 2008). The full inclusion of deaf students means that social networks are accessible, both in person and online, and in both formal and informal settings.

In the survey, we asked questions about the opportunities to engage in student activities and to network. On average, students rated Social Engagement at 2.9.

“I do not get to participate in as many campus activities, especially groups, because services are not easy to come by.”

Diverse Deaf Student Experiences

Each student navigates postsecondary education differently. Although all of the survey respondents are deaf, they may have different experiences with their institutions as a result of their other identities. Our identities often determine the extent to which we are afforded privileges that make navigating institutions, accessing resources, and exerting agency within these systems relatively easy.

The purpose of this section is to provide some insight into how ratings differ by various student characteristics. The data can be used to consider how to make policies and services more inclusive to all deaf students. Improving support for a broad range of deaf students is an important first step toward ensuring educational equity.

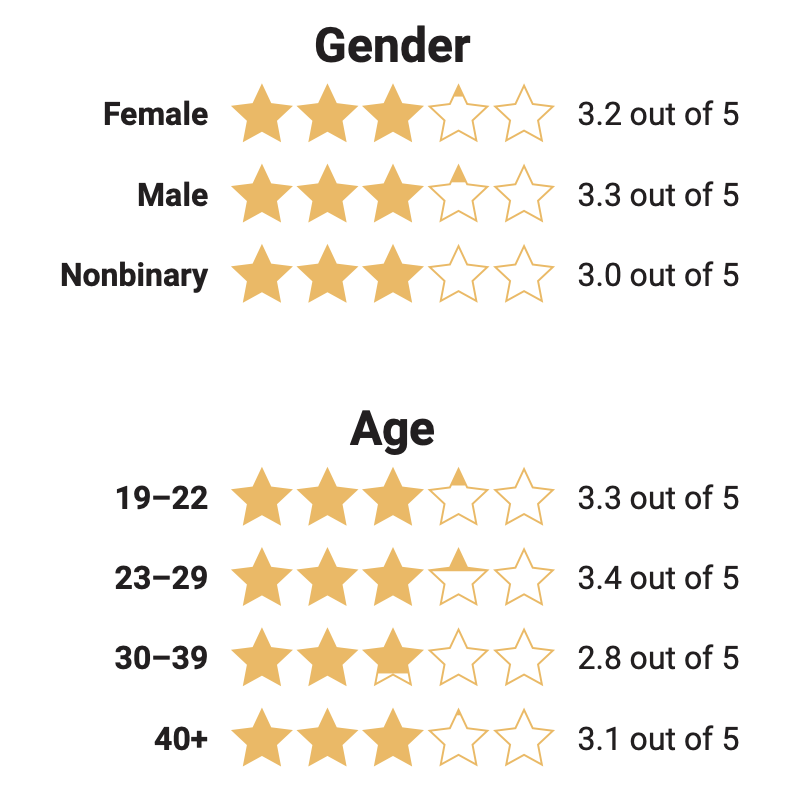

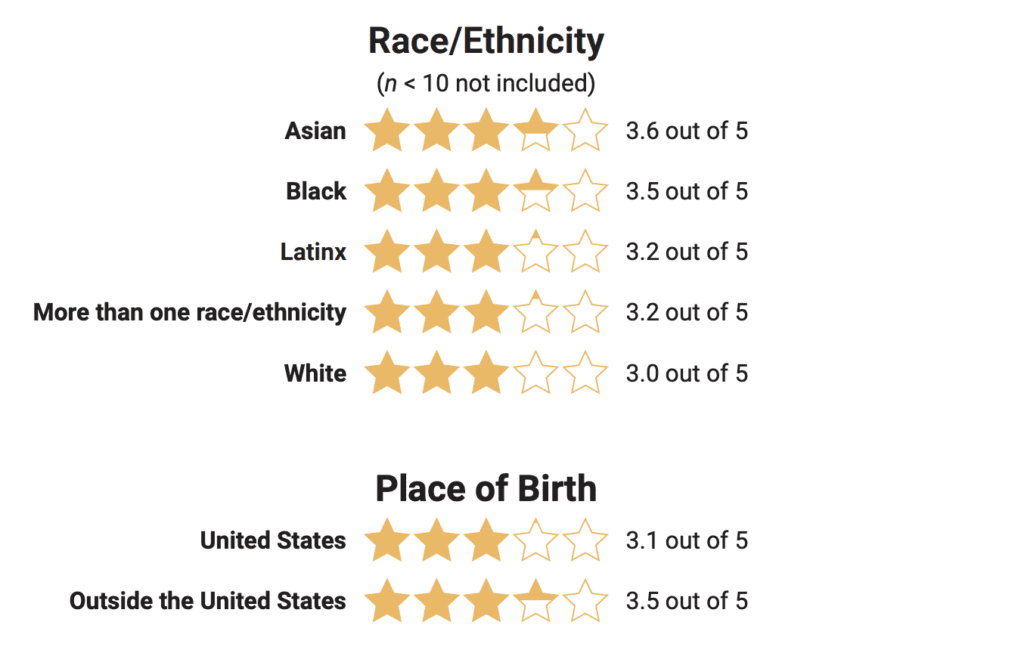

This section provides a breakdown of ratings by various student characteristics. Men and women generally provided similar ratings, but nonbinary and genderqueer students had more negative experiences.

Older students generally provided less favorable ratings for their institutions. Across race and ethnicity, white students provided the lowest ratings, while Asian and black students provided the highest ratings. Students who were born abroad provided more positive ratings than students who were born in the United States.

As with employment outcomes and educational attainment, the most stark differences emerge when comparing across types of disability. Deafdisabled students rated their experiences in higher education worse than deaf students without additional disabilities. Deaf students with visual disabilities and deaf students with mobility or chronic medical disabilities all provided ratings under 3.0.

As these results demonstrate, deaf students can have varying experiences based on their identities.

We “must begin to view students with disabilities through a holistic lens and offer support services, courses, workshops, and everyday conversations that honor their range of experiences with intersectionality” (Kimball et al., 2018).

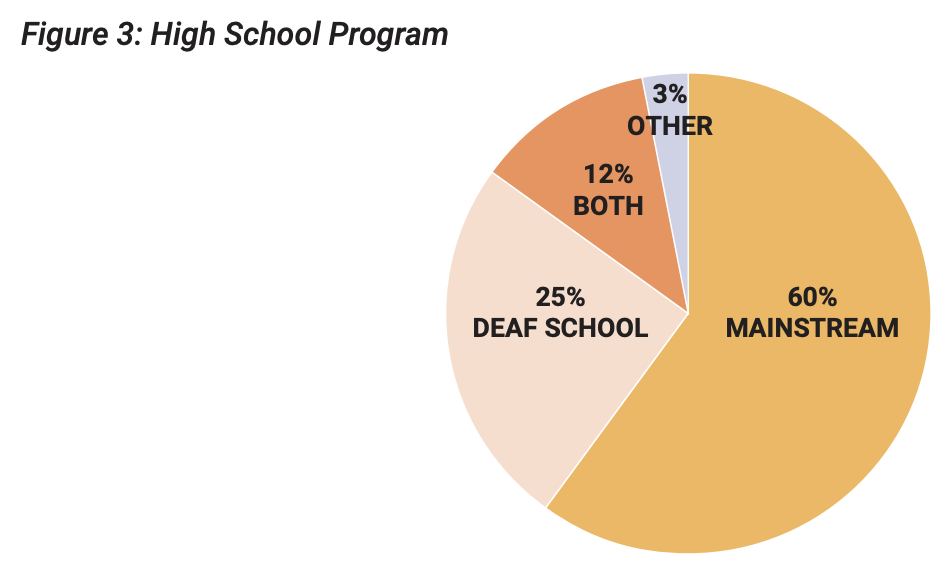

Demographics

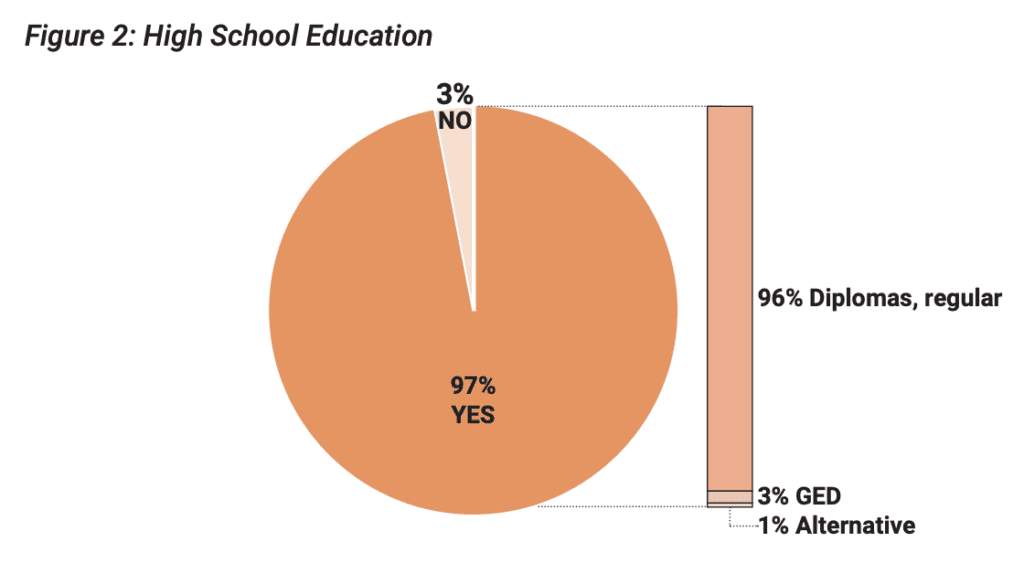

A majority of our survey respondents (97%) graduated high school (Figure 2). Of those, most students reported earning a high school diploma (96%); the remaining students earned a GED (3%) or an alternative diploma (1%). Most students attended mainstream programs during high school, with only 25% attending schools for the deaf (Figure 3).

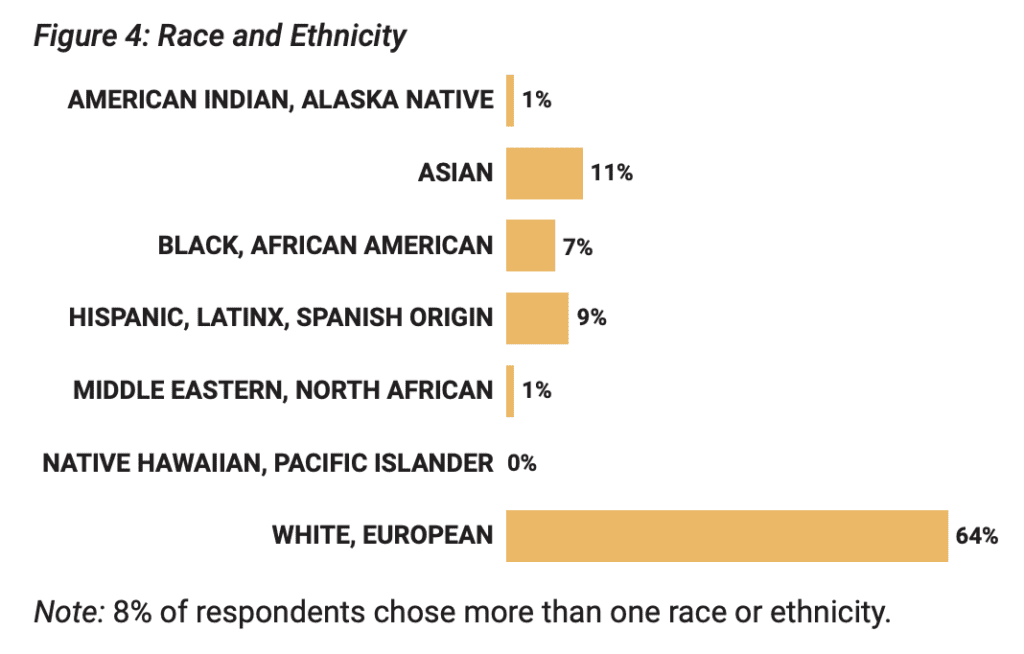

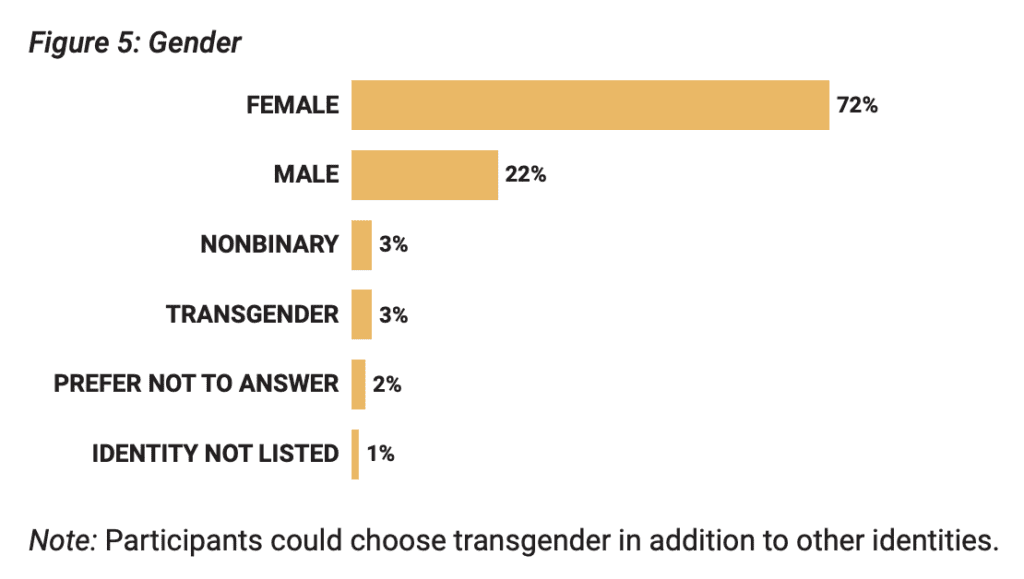

As shown in Figures 4 and 5, this sample was less racially and ethnically diverse (64% white) and more female (72%) than deaf college students nationwide, who are 56% white and 47% female (Garberoglio, Palmer, & Cawthon, 2019). These differences may inhibit the generalizability of the data, so caution is encouraged when interpreting the overall results. The sample also includes deaf foreign exchange students and students who have immigrated to the United States from other countries. A total of 14% of survey respondents reported being born abroad and moving to the United States at age 29 or younger.

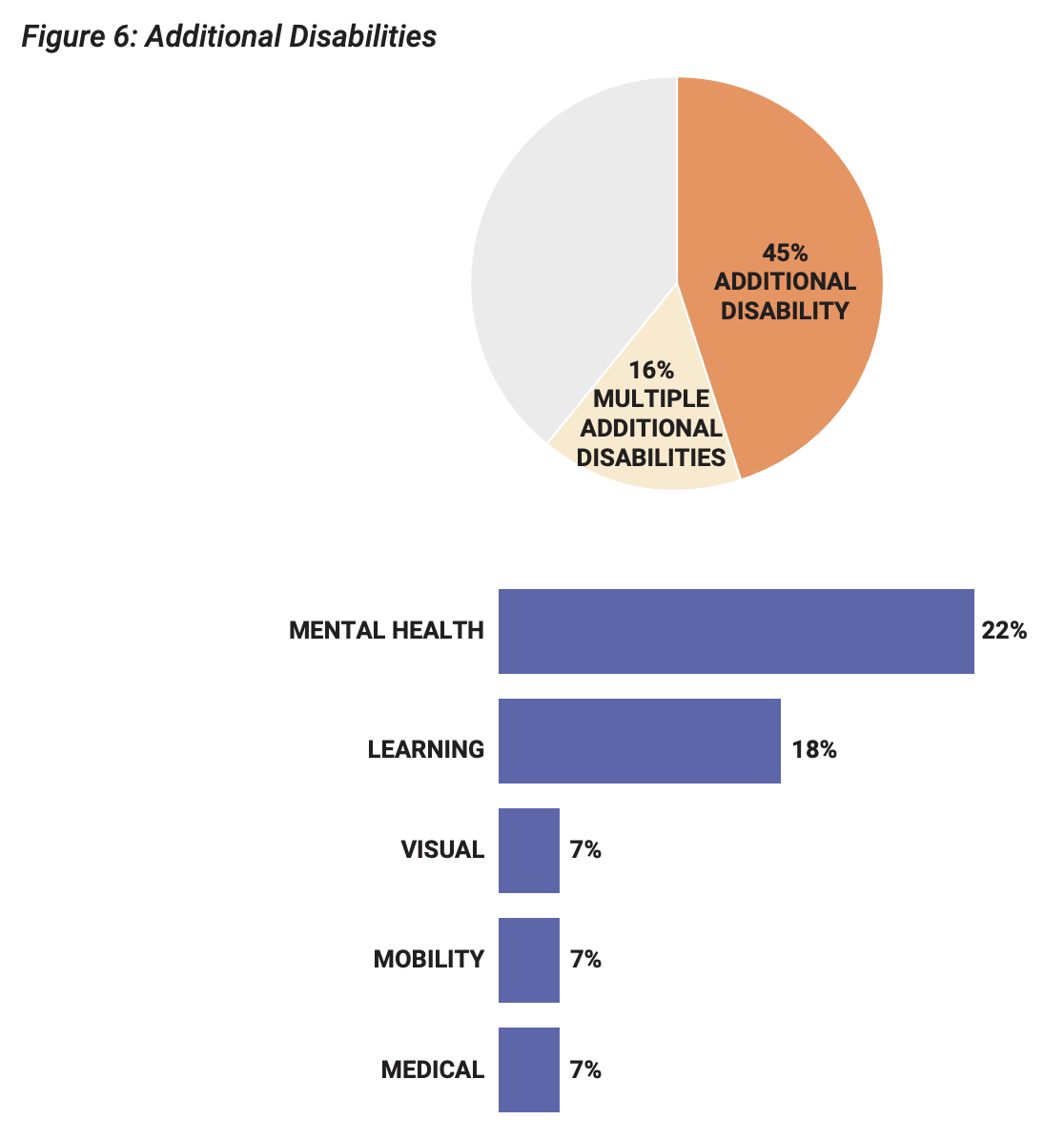

For this survey, 45% of the respondents reported having an additional disability (Figure 6). For comparison, an estimated 40% of deaf children in primary and secondary settings (Guardino & Cannon, 2015) and 50% of deaf adults ages 25–64 have an additional disability (Garberoglio, Palmer, Cawthon, & Sales, 2019). In this dataset, most people reported mental health disabilities (22%), followed by learning (18%), visual (7%), mobility-related (7%), and other medical conditions (7%). Also, 16% of students reported more than one disability category. Given the widespread presence of additional disabilities among deaf students, postsecondary institutions need to be prepared to meet the needs of these diverse students, as each combination results in unique strengths and challenges.

For this survey, 45% of the respondents reported having an additional disability (Figure 6). For comparison, an estimated 40% of deaf children in primary and secondary settings (Guardino & Cannon, 2015) and 50% of deaf adults ages 25–64 have an additional disability (Garberoglio, Palmer, Cawthon, & Sales, 2019). In this dataset, most people reported mental health disabilities (22%), followed by learning (18%), visual (7%), mobility-related (7%), and other medical conditions (7%). Also, 16% of students reported more than one disability category. Given the widespread presence of additional disabilities among deaf students, postsecondary institutions need to be prepared to meet the needs of these diverse students, as each combination results in unique strengths and challenges.

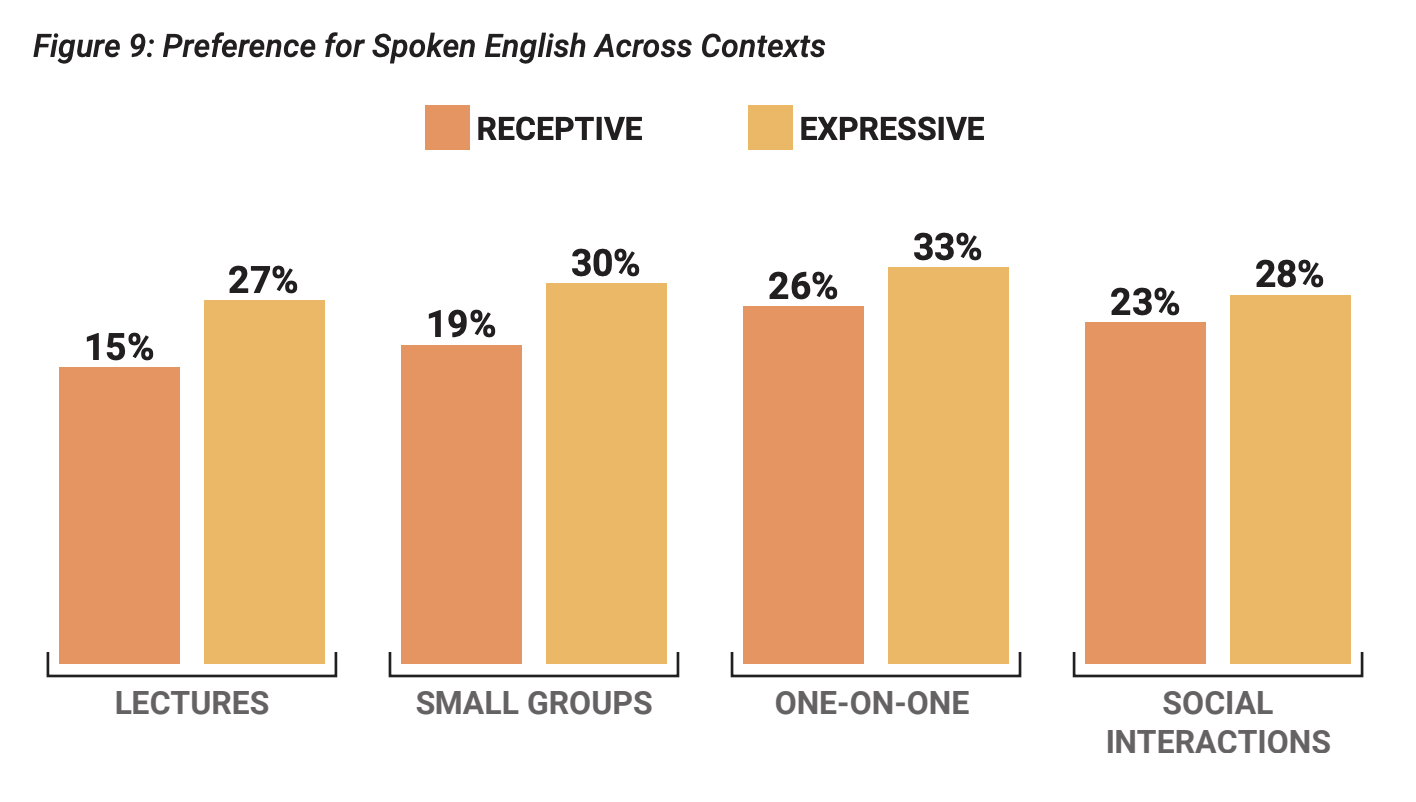

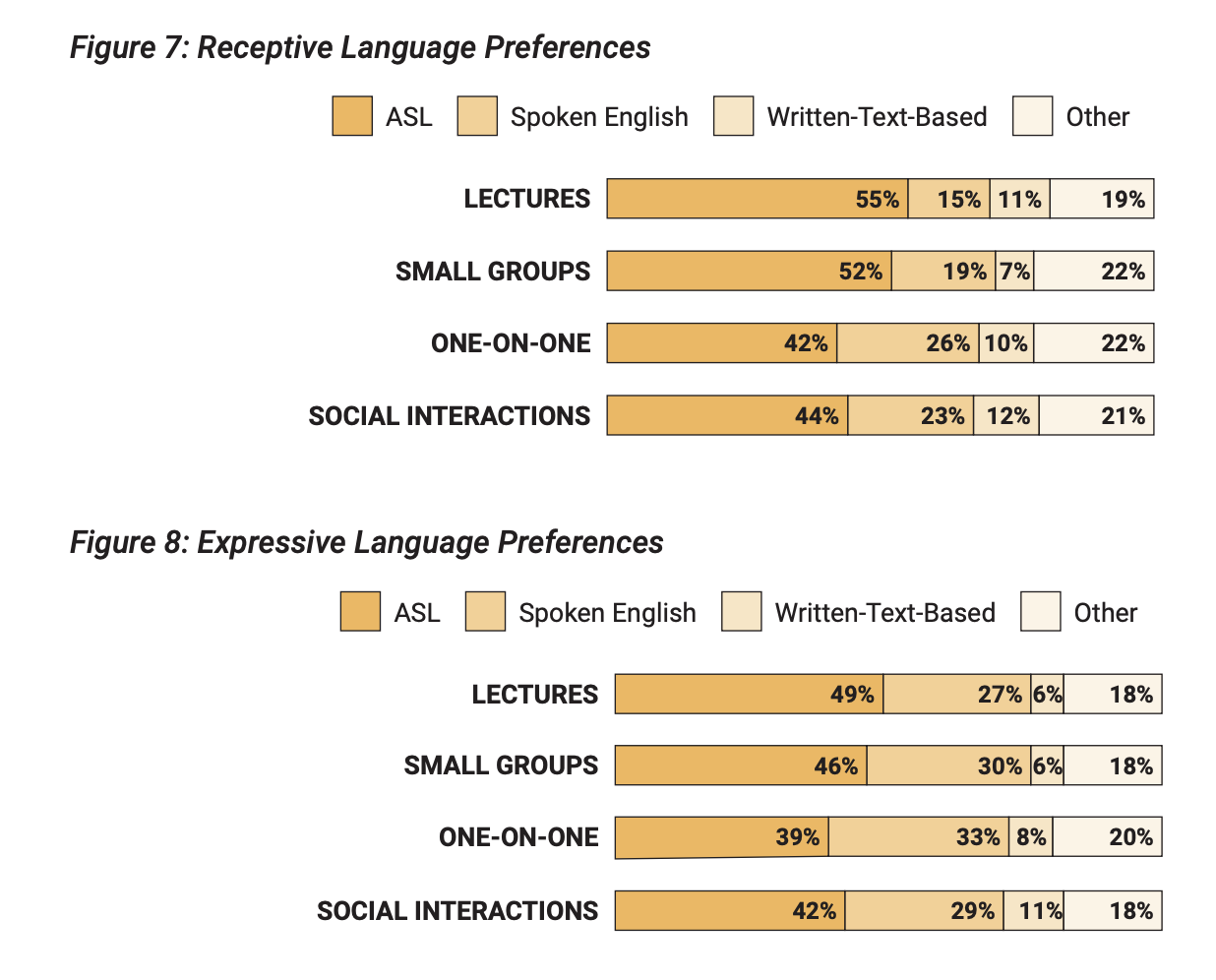

Deaf people use a range of languages and communication strategies that often change across settings and contexts. Deaf people also adjust communication strategies depending on their preferences for receiving information (receptive) and sharing information (expressive).

Deaf people use a range of languages and communication strategies that often change across settings and contexts. Deaf people also adjust communication strategies depending on their preferences for receiving information (receptive) and sharing information (expressive).

Survey participants shared a wide range of communication preferences that shifted depending on context (Figures 7–9). Many students preferred to use sign language in all contexts, but especially for receiving information. Among students who used spoken language, more preferred using spoken languages for sharing information, or voicing for themselves, than for receiving information. Deaf students who prefer to voice for themselves may distrust service providers to relay their ideas accurately. Students reported that they were more comfortable receiving information through spoken language in one-on-one settings than in classes (Figure 9). These findings reinforce the notion that accommodations need to be dynamic instead of fixed and unchanging. Just as deaf students adjust their communication strategies across settings, they also adjust their requests for accommodations.

“The majority of the time, my classes are in very large lecture halls. This makes everything echo or sound muffled.”

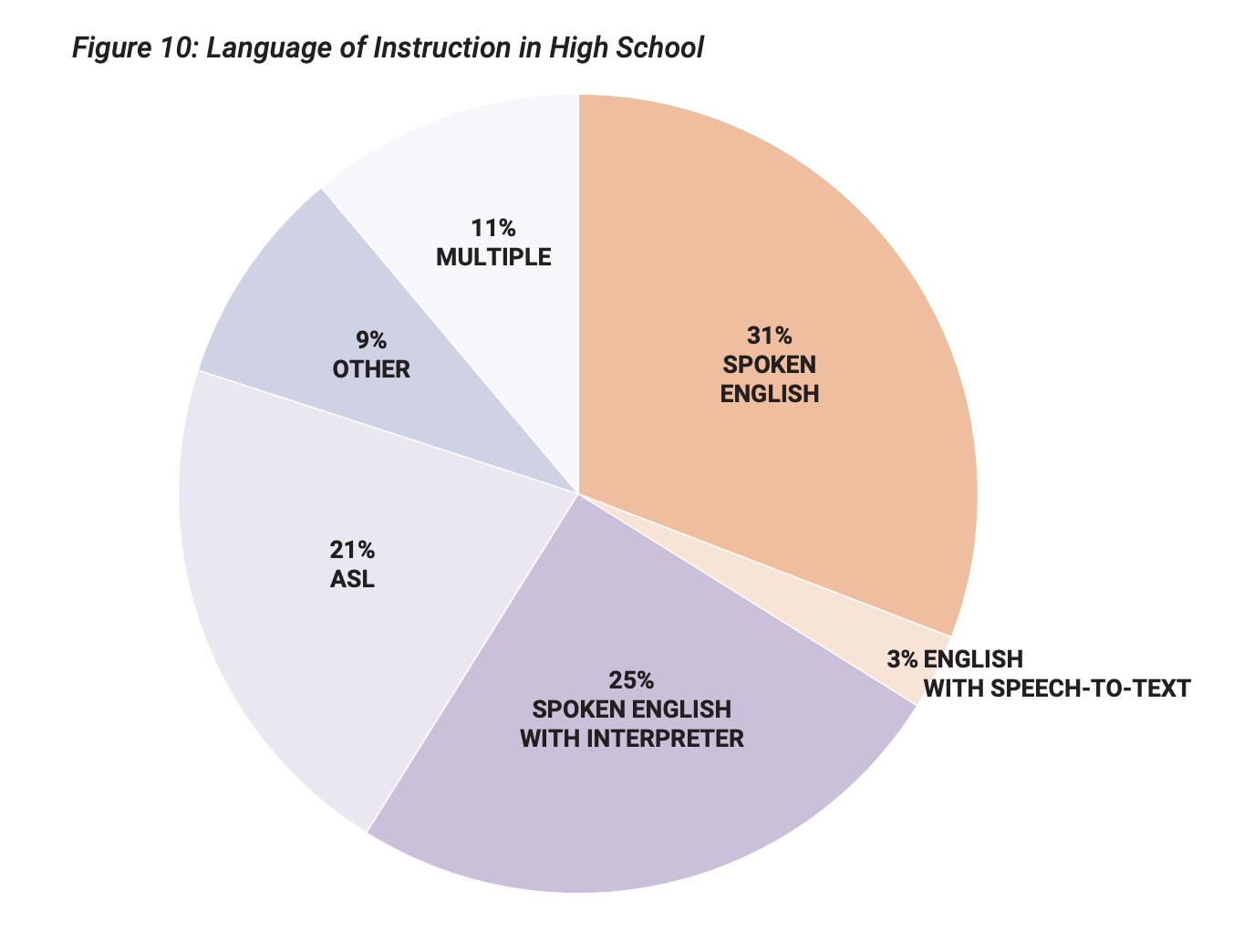

Survey participants experienced a wide range of instructional languages in high school (Figure 10). In this sample, the majority of students (59%) attended classes where spoken English was the instructional language. Specifically, 25% received interpreter-mediated instruction, 3% received text-based instruction via speech-to-text services, and 31% did not have any accommodations. The remaining participants received direct instruction in sign language (21%) or reported a mix of instructional languages (11%).

Survey participants experienced a wide range of instructional languages in high school (Figure 10). In this sample, the majority of students (59%) attended classes where spoken English was the instructional language. Specifically, 25% received interpreter-mediated instruction, 3% received text-based instruction via speech-to-text services, and 31% did not have any accommodations. The remaining participants received direct instruction in sign language (21%) or reported a mix of instructional languages (11%).

The data from this survey suggest that the majority of deaf students might be experiencing language and communication accommodations for the first time in college. Disability Service offices need to consider the needs of these students and how to support them as they figure out what unique combination of accommodations may be the best fit. Although accommodation decisions rely heavily on student requests, it is also the responsibility of disability service professionals to share information about possible accommodations that the students may not know about.

Strategies for Creating ACCESS

The ACCESS survey shows that postsecondary institutions are often unwelcoming and difficult for deaf students to navigate. Frustrations with disability service offices and lack of awareness in the classroom are common.

Students rated institutions 3.2 out of 5 on campus accessibility, leaving plenty of opportunity for improvement. Whether experiencing mainstream education for the first time or experiencing hearing difficulties for the first time, a majority of deaf students surveyed (52%) reported being first-time users of language and communication accommodations in educational settings. This provides a unique challenge to the field and suggests that disability service offices should gather regular feedback and check in with students frequently. Additionally, older deaf students and deaf students with additional disabilities provided lower ratings, suggesting that additional support and attention to these groups may help improve their college experience.

There is an urgent need to create more inclusive campuses for deaf students. The results of this survey can serve as a starting point for evaluating and improving access and inclusion. For each ACCESS category, we recommend the following measures:

To Improve Attitudes on Campus

- Provide faculty members, staff members, and students with ongoing training and information about engaging, interacting, and partnering with deaf students.

- Establish inclusive classroom communication protocols with students to facilitate meaningful interactions and learning opportunities.

- Seek opportunities to include deaf role models on campus; consider partnering with campus clubs and organizations to bring deaf presenters to campus.

To Improve Campus Technology

- Establish standard accessibility requirements for course development and classroom activities.

- Make communication technology available at offices, information desks, campus security, and in residence halls where students are likely to have frequent brief interactions with staff members.

- Create opportunities for students to explore technology and apps that increase accessibility, communication, and autonomy on campus.

To Improve Communications on Campus

- Ensure that important campus announcements are accessible. Consider using multiple systems for communicating campus announcements.

- Include with all communications standard language on how to request accommodations for campus activities and related programming.

- Proactively plan for and grant requests for accommodations for academic and social activities occurring outside the classroom setting.

To Improve the Environment on Campus

- Consider integrating both visual and auditory systems within the architectural and physical surroundings of buildings and classrooms (e.g., visual fire alarms, loop systems in auditoriums, televisions with captions).

- Establish working groups to address the accessibility of information across campus platforms, including emergency communications and audio-visual displays.

- Encourage flexible classroom setups that allow students to maximize visual and auditory access to content, peers, and auxiliary aids.

To Improve Services on Campus

- Outline expectations and responsibilities for students, faculty members, and access providers related to effective implementation of accommodations.

- Establish protocols for collecting regular feedback from students regarding accommodations and auxiliary services; conduct periodic evaluations of services for quality and effectiveness.

- Create and implement institution-wide accessibility policies and practices.

- Collaborate across departments to arrange and pay for services; foster a community responsibility for inclusion.

- Offer, introduce, and train students to use a range of accommodations to maximize experiences and learning across campus.

To Improve Social Engagement on Campus

- Encourage deaf student participation in campus-wide leadership, clubs, and related activities so that deaf students have the opportunity to infuse their values, experiences, and perspectives.

- In student life and residence life offices, increase knowledge about how to request accommodations; shift responsibility for accessibility from deaf students to event planners.

- Encourage networking opportunities, like internships, teaching assistant positions, job shadowing, or mentoring, that will strengthen relationships among faculty members, students, and the larger college community.

Conclusion

Deaf students pursue a college education at a comparable rate to their hearing peers. Yet they are often unable to maximize the collegiate experience because institutions are not prepared to provide equitable access to the full range of programs and services available. The extent to which students are able to start off on the right foot, stay on track, and successfully complete college can be attributed to a combination of institutional and individual readiness (Cawthon et al., 2014). Many institutions uphold their legal responsibilities for providing accommodations, yet they often only satisfy minimum requirements without adequately taking students’ overall learning experience into consideration.

Disability service offices and personnel are often the gatekeepers of engagement for deaf students. Decisions made in this office can create barriers on campus, or dismantle existing barriers. Many decisions about accommodations are made uniformly without a consideration of the individual needs of deaf students across contexts.

This is problematic because what works for one deaf student does not necessarily work for all deaf students. Flexibility in both policy and practice is essential. The diverse experiences of deaf students require disability service professionals to have sufficient knowledge and training to efficiently implement access services that are adaptive and flexible.

Institutions can use the information in this report to design accessible and equitable opportunities for deaf students and to foster an inclusive setting for all students to thrive. Access is more than an accommodation or an afterthought; it’s a multidimensional framework that is woven throughout an institution. Access manifests in the actions, attitudes, and behaviors of leadership, faculty members, staff members, and students on campus. The domains described above are instrumental in designing accessible opportunities and inviting deaf students into the college community.

Take Action!

Disability Service Professionals

Request intensive technical assistance and get a customized action plan to increase your capacity to provide access to deaf students.

Deaf Students

Share this report with your disability service office!

Follow Us on Social Media!

References

Bauman, H. (2014). Deaf space: An architecture toward a more livable sustainable world. In H.- D. L. Bauman & J. J. Murray (Eds.), Deaf gain: Raising the stakes for human diversity (pp. 375–401). University of Minnesota Press.

Brackenbury, T., Ryan, T., & Messenheimer, T. (2006). Incidental word learning in a hearing child of deaf adults. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(1), 76–93.

Bureau of Labor and Statistics. (2019, April 25). College enrollment and work activity of recent high school and college graduates [Press release]. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/hsgec.nr0.htm

Cawthon, S. W., Garberoglio, C. L., Palmer, J. L., Davidson, S., Ryan, C., & Johnson, P. (2020). Measuring accessibility of postsecondary education and training for deaf individuals: A proposed conceptual framework. Future Review: International Journal of Transition, College, and Career Success, 1(3), 1–14.

Cawthon, S. W., & Leppo, R. (2013). Accommodations quality for students who are d/Deaf or hard of hearing. American Annals of the Deaf, 158(4), 438–452.

Cawthon, S. W., Schoffstall, S. J., & Garberoglio, C. L. (2014). How ready are postsecondary institutions for students who are d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing? Educational Policy Analysis Archives, 22(13).

Covell, J. A. (2007). The learning styles of deaf and non-deaf pre-service teachers in deaf education. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section A. Humanities and Social Sciences, 68(4), 1414.

Crowe, K., McLeod, S., McKinnon, D., & Ching, T. (2015). Attitudes toward the capabilities of deaf and hard of hearing adults: Insights from the parents of deaf and hard of hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf, 160(1), 24–35.

Edwards, C., & Harold, G. (2014). DeafSpace and the principles of universal design. Disability and Rehabilitation: An International, Multidisciplinary Journal, 36(16), 1350–1359.

Garberoglio, C. L., Palmer, J. L., & Cawthon, S. (2019). Undergraduate enrollment of deaf students in the United States. Austin, TX: National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, The University of Texas at Austin. https://www.nationaldeafcenter.org/resource/undergraduate-enrollment-deaf-students-united-states

Garberoglio, C. L., Palmer, J. L., Cawthon, S., & Sales, A. (2019). Deaf people and employment in the United States: 2019. Austin, TX: National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, The University of Texas at Austin. https://www.nationaldeafcenter.org/resource/deaf-people-and-employment-united-states

Guardino, C., & Cannon, J. E. (2015). Theory, research, and practice for students who are deaf and hard of hearing with disabilities: Addressing the challenges from birth to postsecondary education. American Annals of the Deaf, 160(4), 347–355.

Hintermair, M. (2008). Self-esteem and satisfaction with life of deaf and hard-of-hearing people—A resource-oriented approach to identity work. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13(2), 278–300.

Kimball, E., Vaccaro, A., Tissi-Gassoway, N., Bobot, S. D., Newman, B. M., Moore, A., & Troiano, P. F. (2018). Gender, sexuality, & (dis)ability: Queer perspectives on the experiences of students with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 38(2).

Lederberg, A. R., Prezbindowski, A. K., & Spencer, P. E. (2000). Word-learning skills of deaf preschoolers: The development of novel mapping and rapid word-learning strategies. Child Development, 71(6), 1571–1585.

National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes. (2019). Evidence-based technical assistance. National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, The University of Texas at Austin.

Smith, D. H. (2013). Deaf adults: Retrospective narratives of school experiences and teacher expectations. Disability & Society, 28(5), 674–686.

Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2019). Digest of education statistics 2017 (NCES 2018- 070). National Center for Education Statistics.

Vignes, C., Godeau, E., Sentenac, M., Coley, N., Navarro, F., Grandjean, H., & Arnaud, C. (2009). Determinants of students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 51(6), 473–479.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.